Southeast Asia and COVID-19 Vaccines Explained

By Richard Maude

Published on 21st June 2021

Read in 10 minutes

As new Asia Society analysis recently explored, a surge of COVID-19 infections in Southeast Asia is costing lives and threatening to derail recovery from last year’s painful recession.

Southeast Asia demonstrated in 2020 that it could keep the worst of the pandemic at bay through lockdowns and other mobility and social distancing restrictions.

But Southeast Asia also needs strong vaccination programs to allow it to move past the acute phase of the pandemic, keep on top of highly infectious new variants and ensure economies can stay open.

To date, Southeast Asia has been held back by vaccine shortages and other challenges.

That’s about to change. A coming revolution in vaccine production and donation might just be in time for Southeast Asia as the region works desperately to ramp up vaccination programs.

But Southeast Asia’s lower-income countries will still need significant external donor support, not just for vaccines but to turbo-charge vaccination rates, overcome vaccine hesitancy, and manage the logistical challenges of the so-called “last mile” of delivery.

Skip to section:

A slow start Where are all the vaccines? What vaccines are going to Southeast Asia and how? Donated vaccines Purchased Vaccines Turning on the vaccines tap About the AuthorA slow start

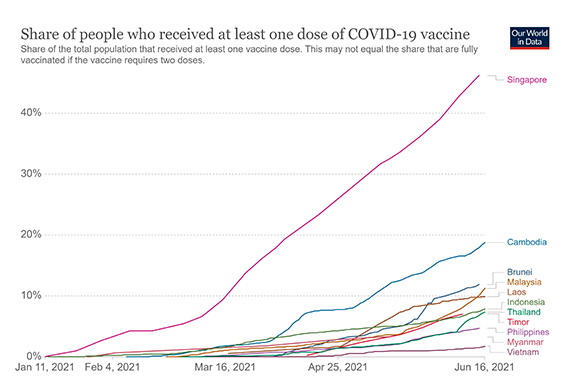

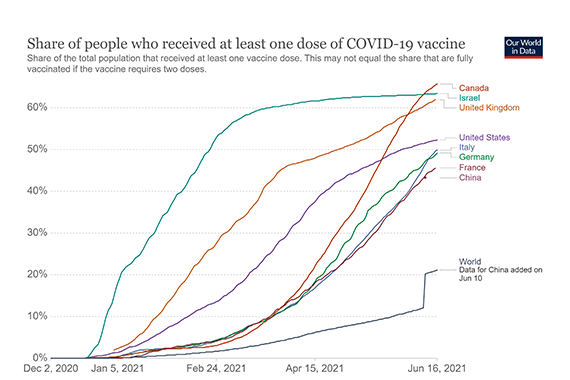

Except for Singapore, national vaccination rates in Southeast Asia as a percentage of populations are low.

Source: ourworldindata as of 16/06/2021

Factors affecting vaccination programs vary considerably from country to country, but include

- significant vaccine supply shortages

- large and/or dispersed populations that complicate “last mile” delivery

- under-resourced public health systems and other bureaucratic constraints

- lack of financial wherewithal to purchase large numbers of vaccines, in the case of the poorest countries in the region

- conflict, in the case of Myanmar following the military’s coup

- limited local vaccine production capabilities

- vaccine hesitancy, with reasons ranging from concerns from Moslems that vaccines might not be halal to doubts about the efficacy and safety of Chinese made vaccines. In the Philippines, the troubled introduction of a Dengue vaccination in 2016 also still reverberates.

Where are all the vaccines?

Global production has ramped up quickly as vaccines have been developed and approved.

One industry estimate suggests more than three billion doses of vaccines will have been produced globally by the end of June, with production rates continuing to rise through the year. New vaccine candidates are also being moved at a steady clip through development and safety trials.

To date, however, wealthy countries have monopolised the purchase of vaccines. As of mid-May, only 0.3 per cent of the total vaccines administrated globally had gone to low-income countries.

According to the Duke Global Health Innovation Centre, wealthy countries purchased enough doses in 2020 to vaccinate their populations several times over, even before any vaccine candidates were approved.

These deals have meant that a “smaller piece of the pie is available for low- and middle-income countries and for equity focussed partnerships like COVAX”.

It’s no surprise therefore that it’s mostly wealthy countries that sit atop the global vaccination table.

Source: ourworldindata as of 16/06/2021

The global vaccine supply picture is starting to change. Indeed, we are on the cusp of a revolution in vaccine production and donation. In the meantime, though, Southeast Asian countries still don’t have enough doses to vaccinate most of their populations.

What vaccines are going to Southeast Asia and how?

The vaccine story in Southeast Asia is fast-moving, a complex mix of bilateral and multilateral donations, purchase orders with all major current COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers, emerging local production, home-grown vaccine development, and even private sector fund-raising.

Until very recently, Southeast Asia has been entirely dependent on external suppliers for its vaccine programs.

China quickly emerged as one of the largest source countries for the region, with the first Sinovac vaccines arriving in Indonesia in December 2020.

Indeed, perhaps nothing illustrated China’s position as a first-mover as strongly as the very public vaccination of Indonesian President Joko Widodo in mid-January, well before World Health Organization approval of Sinovac for emergency use and at a time of swirling doubts about Sinovac trial data and its efficacy.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo receiving the coronavirus vaccine in January 2021 – Facebook

China’s pandemic aid, including vaccine supply, has met urgent and genuine needs in Southeast Asia. It has also bought China goodwill and supported China’s political, security and economic objectives at a time of sharp strategic contestation in the region.

Still, other global vaccine manufacturers are also now well-represented in Southeast Asia’s direct purchase orders and through the COVAX initiative.

And a series of major announcements by the Biden Administration has positioned the United States to match or surpass Chinese vaccine donations to Southeast Asia.

Donated vaccines

COVAX AMC

The COVAX facility is a global risk-sharing mechanism for pooled procurement and equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. It is the primary multi-lateral mechanism striving to overcome vaccine nationalism.

Support for lower-income countries is provided through the COVAX Advance Market Commitment (COVAX/AMC) financing instrument, which aims to provide sufficient vaccines for participating countries to vaccinate almost 30 per cent of their populations, starting with high-priority target groups like front-line health care workers and the elderly or otherwise vulnerable.

Seven lower-middle income countries in Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Philippines, Timor-Leste and Vietnam) are eligible countries under the COVAX AMC arrangement.

The United States, the European Union, Japan and Australia are among major donors to the facility.

COVAX has purchase agreements with a range of vaccine producers and is now delivering regularly into Southeast Asia. But most Southeast Asian participants did not begin to receive vaccines until March-April.

According to COVAX data, deliveries of vaccines as of 9 June have ranged from some 4.9 million doses for Indonesia down to 124,800 doses for Timor-Leste.

Across all eligible Southeast Asian countries, initial deliveries are small compared to the need.

Like everyone, COVAX has grappled with delays in securing supplies. In particular, India’s decision to re-focus its huge vaccine production capability on its urgent domestic needs created a significant short-term shortfall in vaccine doses (some 190 million doses to end-June) for the COVAX initiative.

The Quad Indo-Pacific vaccines partnership

India’s withdrawal from the export market could, if it is long-lasting, also affect the newly announced Quadrilateral Security Dialogue Indo-Pacific vaccines initiative, the centrepiece of which was financing and other support to boost Indian production of vaccines for export.

If this gap can be plugged, the initiative wants to supply one billion doses to the Indo-Pacific by the end of 2022.

Direct bilateral donations

Despite large funding backing for COVAX, until recently the United States was not making direct vaccine donations.

With vaccination rates rising in the United States, the Biden Administration has dramatically stepped-up US global leadership on the pandemic, beginning with a down payment of 80 million donated doses from US stockpiles.

Some seven million doses from the first 25 million of this allocation will be shared among South and Southeast Asian countries, either through COVAX or directly, with Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand benefitting (the White House fact sheet does not break these numbers down further).

On 10 June, Biden also announced his Administration would purchase an additional 500 million doses from Pfizer and donate them to nearly 100 lower-income countries – the largest single purchase and donation of COVID-19 vaccines by any single country.

It is not yet clear how many of these will go to Southeast Asia, but the United States clearly is now in position to match or surpass donations by China.

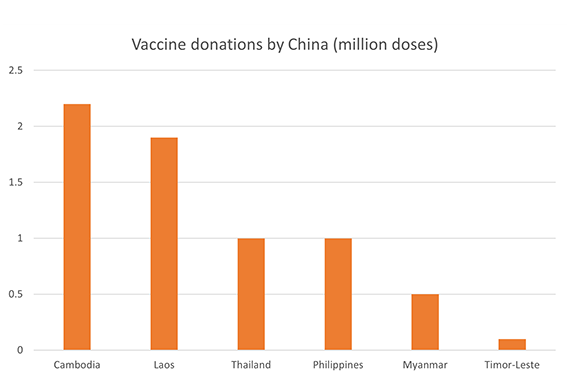

China is a significant direct donor of vaccines and other COVID-related medical supplies and support, including to Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines and Timor-Leste.

Precise numbers are difficult to verify as China does not appear to have a single central official summary of donated vaccines.

The Beijing-based consultancy firm Bridge estimates China has donated some 22.8 million vaccine doses globally, of which 14.25 million have gone to the Asia-Pacific. These donations are small compared to China’s commercial agreements to export some 742 million doses globally (data as of 11 June).

China has also said it will provide 10 million vaccine doses to COVAX.

Based on an Asia Society survey of media reporting as of 13 June, China’s estimated donations of vaccines to Southeast Asian counties range from 100,000 for Timor-Leste up to 2.2 million for Cambodia.[1]

Source: BridgeBeijing.com

China’s early supply of donated vaccines allowed recipient countries to get vaccine programs underway for front-line health workers and other high-priority groups at a time when other supplies were slow in arriving.

As of 29 May, India had donated 1.7 million vaccine doses to Myanmar (prior to re-orienting production to domestic needs, Indian vaccines were also supplied through COVAX to Cambodia and Laos).

Australia is providing East Timor with vaccines from national stocks and is partnering with UNICEF to deliver vaccines for six million people in Timor-Leste and Pacific island nations, and 9 million people in other Southeast Asia countries.

Australia has also announced a 20 million dose contribution to the G7 vaccine initiative (see below) with a focus on Indo-Pacific countries.

The European Union, a generous donor to public health responses to the pandemic in Southeast Asia, has prioritised COVAX over direct bilateral donations.

Japan recently announced it will send one million doses to Vietnam and may make similar donations to other Southeast Asian countries.

[1] These estimates are broadly in line with the Bridge vaccine tracker.

Purchased Vaccines

Southeast Asian countries are also busy buying vaccines. The Duke Global Health Innovation Centre vaccines “speedometer” is a useful tracking tool for these.

Indonesia is the biggest buyer in the region, with advance purchase orders (as of 11 June) for a hefty 255.5 million doses, still not enough to cover its population of 276 million people.

Other purchase commitments vary considerably: a sample as of 11 June includes the Philippines (148m doses), Malaysia (66.3m) and Vietnam (80m). Cambodia records only 3.3 million purchased does.

Chinese vaccines account for the lion’s share of Indonesian advance market commitments, including Sinovac in bulk form. Indonesia also hosted a phase three trial for Sinovac’s vaccine.

Other Southeast Asians with large purchase commitments have more balanced portfolios, with Pfizer, Moderna, Russia’s Sputnik V, AstraZeneca, and Novavax all represented across the region and new vaccine candidates being watched closely.

Vietnam has not to date purchased any Chinese vaccines but recently approved Sinopharm’s vaccine for use.

These purchase commitments do not, of course, equate to vaccines delivered in the current very tight global market. Most countries report shipment delays and/or reduced numbers of doses.

Turning on the vaccines tap

Global supplies of vaccines are likely to rise quite quickly, even over the course of 2021, as vaccination rates jump in wealthy countries, production of existing vaccines is ramped up and new vaccines come on line.

COVAX argues that “if the world’s leaders rally together”, the original COVAX objectives – delivery of 2 billion doses of vaccines worldwide in 2021, and 1.8 billion doses to 92 lower-income economies by early 2022 – are still well within reach.

Southeast Asia is also moving to reduce its dependence on external manufacturers. AstraZeneca vaccines, for example, are just starting to be produced in Thailand for local and regional use.

Vietnam also wants to develop an indigenous manufacturing capability. And Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand have homegrown vaccines in development.

In recent weeks, there have also been welcome signs of the global ambition needed to accelerate vaccination programs in the developing world.

As noted above, the Biden Administration has announced its intention to step up global leadership on the pandemic.

At the 21 May EU-G20 Global Health Summit, the European Union announced it would donate 100 million doses of vaccines to low-and middle-income countries, including through COVAX. Major manufacturers also pledged additional “no profit” and “lower price” vaccines.

The COVAX summit in Japan on 2 June raised another $US2.4 billion, enough for COVAX to secure 1.8 billion free vaccine doses for lower-income countries in 2021 and early 2022.

And the June G7 summit committed to sharing “at least 870 million doses” over the next year, primarily channelled through COVAX “towards those in greatest need”. The 500 million doses announced by President Biden on 10 June will form the lion’s share of this new commitment.

The G7 summit also committed to several other ambitious but broad objectives, including boosting supply of raw materials, tests and personal protective equipment, along with “new partnerships based on voluntary licensing and technology transfer” to support production of vaccines in third countries.

While the medium-term outlook on vaccines production and supply looks hopeful, global needs are very high right now.

The international aid organisation Oxfam, for example, criticised the G7 outcome on vaccines as a “drop in the bucket” and called for immediate waivers of intellectual property rights.

And despite new donor pledges, there’s still an urgent need for more grant financing to fight the pandemic globally.

The World Bank and IMF leadership have said that as much as $US50 billion of financing is needed to achieve more equitable access to vaccines, tests and treatments.

Even with stronger supply, some Southeast Asian countries will struggle to quickly ramp up national vaccination programs.

It would be a double tragedy for the region if the problem shifts from too few vaccines to too many to be used effectively.

Much of the region will need ongoing donor assistance to overcome vaccine hesitancy, expand vaccination services, and solve “last-mile” logistical and storage challenges.

Especially for the largest Southeast Asian countries, like Indonesia and the Philippines, and the poorest, such as Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar and Timor-Leste, keeping up with variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and continually vaccinating populations, will be a gargantuan task.

Some already rely heavily on external funding and UN procurement systems even for routine immunisations.

Finally, like the rest of the world, Southeast Asia will have to make a complex shift towards living with COVID-19.

Vaccines are critically important, but not the whole story. The region will need to keep mobility and social distancing measures and robust testing and contact tracing capabilities in their COVID response tool kits. Without such measures, fresh outbreaks could get away from the region quickly, even as vaccination rates rise.

About the Author

Richard Maude is Executive Director of Policy at Asia Society Australia and a Senior Fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute. Mr. Maude joined Asia Society after a 30-year career as an Australian diplomat and intelligence official. He is a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Director-General of the Office of National Assessments, and senior foreign policy adviser to Prime Minister Julia Gillard.