Omicron in Southeast Asia: Vaccines, Politics and Health Reform

By Ivanna Ting Mei Sim, Khor Swee Kheng, and Sean Chern Choong Thum

Published on 4th March 2022

Read in 5 minutes

On 24 November 2021, South Africa reported the world’s first Omicron case. Only five weeks later, Omicron was estimated to account for 95 per cent of all COVID cases in the United States, displacing Delta as the dominant strain. Southeast Asia has not been spared – caseloads have surged across the region since January 2022.

Fortunately for the region, increased cases have not translated into large loss of life. This is due to Omicron being more infectious, but causing milder disease due to its lower intrinsic pathogenicity and with greater population immunity after vaccinations and boosters. Hence, despite increased hospitalisation rates alongside caseloads, we are seeing a lower case fatality rate in all regional countries when compared to the 2021 Delta wave, which is a reassuring “decoupling”.

Even so, while learning to live with Omicron, Southeast Asia is missing a historic opportunity to reform public health systems. Now is the time for ASEAN countries to put public health funding on a sustainable and equitable basis, invest in human capital and accelerate digital health programs.

Skip to section:

Southeast Asia Needs More Vaccines Omicron Response = Science + Politics Start Health Reforms, Today Turbulence in 2022 About the AuthorsSoutheast Asia Needs More Vaccines

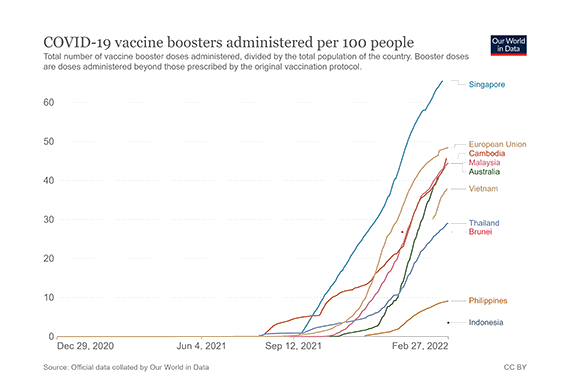

Vaccines and boosters are important to combat Omicron. However, many Southeast Asian countries were slow to obtain their first batches of COVID-19 vaccines in 2021 as richer countries hoarded available doses. The delay in primary vaccinations has translated into a delay in booster vaccinations. As of 28 February, the vaccine tracker in Our World in Data shows that Southeast Asia lags behind rich countries in booster coverage (9-42 per cent compared to 52-55 per cent in the European Union, with the exception of Singapore at 66 per cent).

Booster doses administered per 100 people in select ASEAN countries, Australia, and the European Union Source: Our World in Data

To increase the vaccination and booster rate, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines have developed private schemes. However, this poses three main issues. First, there is a backlog of vaccines as major vaccine manufacturers prioritise government hospitals, not private hospitals. Second, the private sector may focus on high-income patients only, widening vaccine inequity. And third, vaccinations could be the “ultimate public good”, and privatizing vaccination programs may lead to a slippery slope of privatizing other healthcare services, which could reduce healthcare access in the long-term.

Two notable features from Southeast Asia’s COVID vaccination programs so far are the absence of meaningful domestic production of vaccines and the lack of discussion around regional pooled procurement. In the early days of vaccinations in 2021, there was significant talk of home-grown vaccines in Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, and technology transfers of Chinese vaccines to Indonesia and Malaysia. However, most of the vaccines being used in the region are still manufactured overseas and imported.

The ASEAN Secretariat and ASEAN Member States have convened meetings on pandemic recovery and regional trade cooperation, notably the ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework (ACRF), which was approved in November 2020. But regional pooled procurement for COVID vaccines for 650 million people in Southeast Asia is not yet making meaningful progress.

Omicron Response = Science + Politics

Fighting Omicron cannot be solely based on science, vaccines, and boosters. After two years of the pandemic, Southeast Asians want to just get on with their lives, Omicron or no Omicron. But economic and social recovery requires good political choices to be made, alongside good scientific choices.

Whether consciously and intentionally or otherwise, leaders of Southeast Asian countries have shifted the goals of the pandemic response slowly and invisibly, away from “preserve lives first” to “economic recovery first”. Naturally, there is a difference of degree between different countries, but the overall trend to prioritise livelihoods over lives is clear.

For example, each Southeast Asian country has developed unique economic strategies to combat COVID-19 and to reopen their societies. Thailand, a country which relies heavily on tourism, started the Phuket Sandbox Program in July 2021 to allow vaccinated international travellers into the country, roughly similar to Langkawi, Malaysia, and Bali, Indonesia. Singapore has opened Vaccinated Travel Lanes (VTL) with several countries to maintain its status as the travel and financial hub. Malaysia is now in Phase 4 (the last phase) of the National Recovery Plan, as close to normality as possible, with Omicron still raging in February 2022.

The longer the pandemic, the higher the pressure to reopen societies, countries, and borders. Making these decisions during a surging Omicron wave is difficult, so leaders must do several things all at once. First, they must base their decisions on the best available scientific and epidemiological evidence on COVID and Omicron. Second, they must communicate these decisions (and their criteria) to the public in non-paternalistic ways to assign appropriate responsibility to their citizens. Third, they must provide over-arching guiding strategies for reopening societies, rather than provide a collection of reactive or knee-jerk decisions.

Doing all that requires a careful mixture of science and politics. Omicron and COVID cannot be fought with science alone – the challenge requires political will, skill, and courage.

Start Health Reforms, Today

A wise person once asked a young farmer, “How long will this tree take to bear fruit?”. “Twenty years”, came the reply. “Then we should plant it immediately”, said the wise person.

In 2022, a similar situation presents itself to Southeast Asian countries wanting to reform their health systems. The region is missing a historic opportunity to reform health systems because COVID is no longer the force that unites political parties, voters, taxpayers, citizens and Health Ministries or Departments with one voice. The “shock value” of COVID is diminishing – not even surging case numbers of Omicron is persuading citizens across the region to get booster shots or to be more circumspect in international travel.

In our opinion, no Southeast Asian country has begun concrete measures to reform or strengthen their national health systems (beyond reports, white papers, or political promises). There are three specific areas of reform that are needed. First, health financing has to be increased, diversified and made more sustainable. This must be paired with appropriate changes in the political economy of healthcare, to bring the public and private healthcare systems closer together. Countries must prevent a divergence of outcomes and spending. Private hospitals should not spend more money and deliver better outcomes than public hospitals. In effect, health should be for all, not for the rich.

Second, every Southeast Asian country must carefully consider strategies to increase their human capital. In practical terms, this means that countries must train more doctors, nurses, paramedics, epidemiologists, and allied healthcare professionals (HCPs). And then countries must incentivize them appropriately, with proper career progression pathways, opportunities for higher education, and equitable pay. And countries must prevent a brain drain from the public to private, or lose their HCPs to rich countries.

Third, countries must build their digital health infrastructure. This begins with proper regulation, standards and codes of practice, and continues with conscious efforts to increase quality and access while reducing cost. For example in the Philippines, in addition to developing COVID-19 case management, Filipino HCPs have implemented COVID-19 mitigation measures for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Tuberculosis (TB), and malaria using digital health services. These measures are important globally, but more so in Southeast Asia where some countries have a shortage of doctors per capita. Availability of digital health increases accessibility of healthcare in many regions while empowering patients to manage their own health.

Turbulence in 2022

2022 is a big year for Southeast Asia. Timor-Leste (in March) and the Philippines (in May) are expected to hold presidential elections, with a possibility of federal elections in Malaysia. The civil war in Myanmar continues unabated. Severe natural disasters have hit Malaysia (floods) and Indonesia (earthquake) in the first two months of the year. And the regional economic recovery may face headwinds, with the Russia-Ukraine crisis potentially affecting recovery, and the South China Sea being a potential flashpoint for superpower rivalry.

In such circumstances, it would be difficult for any country to keep Omicron, COVID and health reforms on top of the political and public agenda. But the costs of not addressing COVID while reforming health systems will be much more difficult to bear.

About the Authors

Ivanna Ting Mei Sim, Khor Swee Kheng, and Sean Chern Choong Thum are members of the Malaysian Health Coalition.

The Malaysian Health Coalition is an apolitical coalition of Malaysian health professional societies, health professionals and citizens dedicated to improving the health of Malaysians, strengthening the Malaysian health system, and supporting Health in All Policies.