The Pandemic and ASEAN

By Richard Maude

Published on 9th November 2022

Read in 4 minutes

After two-and-a-half gruelling years, Southeast Asia has opened its economies and borders and is learning to live with COVID-19. The Asia Society Policy Institute and Asia Society Australia are therefore bringing our long-running Southeast Asia and COVID-19 project to a close. As we do so, we briefly revisit earlier project analysis of the pandemic’s effect on the region’s geo-politics, economics, and society.

In April 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic began its deadly march across Southeast Asia, the region’s leaders met virtually for an emergency summit. Leaders declared their determination to “remain united, and to act jointly and decisively to control the spread of the disease while mitigating its adverse impact on our people’s livelihood, our societies and economies”.

In the months to come, the pandemic would pose the most severe social, economic, and political test for Southeast Asia, and for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), since the 1997 Asian financial crisis. How well did ASEAN perform in such challenging circumstances?

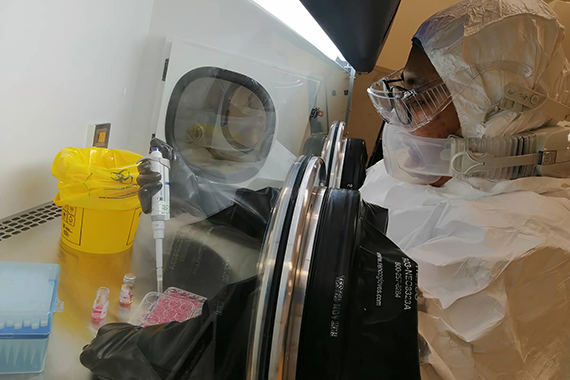

In part, ASEAN leaders and governments lived up to their declaration. The dense web of ASEAN cooperation and dialogue on public health issues, informed by the region’s previous experience with SARS, supported valuable information sharing. ASEAN created new mechanisms to tackle public health emergencies and agreed to an economic recovery plan. Strong partner support for pandemic-related initiatives reinforced “ASEAN centrality” – the idea that ASEAN should remain at the core of the Indo-Pacific’s diplomatic architecture.

Writing for this project in early 2021, Sharon Seah therefore described 2020 as a “productive year” for ASEAN. The group established a COVID-19 response fund, to which the region’s external partners have made donations, completed a “strategic framework” with a set of high-level principles to guide future responses to public health emergencies, and established a regional reserve of medical supplies designed to help the “surge capacity of one or more” ASEAN member. Reserve supplies (such test kits, personal protection equipment and essential medical supplies) are held and controlled by national governments, not pooled centrally. So, the real test of the initiative will come in the next crisis.

A new ASEAN Centre for Public Health Emergencies and Emerging Diseases (ACPHEED) was announced. Donors, notably Japan ($US50m) and Australia ($A21m), backed ACPHEED heavily. Sometimes badged as a regional centre for diseases control, the new entity is intended to help strengthen ASEAN’s ability to detect and respond to public health emergencies. This ambitious initiative has been slow to get off the ground, but there is now agreement that Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam will jointly shepherd the centre’s work. ACPHEED’s challenge is to demonstrate it can make a real difference in the preparation for, and management of, future health crises.

Meeting in Hanoi in November of 2020, ASEAN leaders also agreed to ensure the smooth flow of essential goods, refrain from imposing unnecessary non-tariff measures and work to build the resilience of supply chains. And, indeed, apart from some early, knee-jerk restrictions on essential food items, ASEAN resisted the temptation of economic nationalism and protectionism.

The finalisation of the giant Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) trade agreement, drawing ASEAN together with Australia, New Zealand, China, Japan and the Republic of Korea, took on renewed urgency. So too did the fuller participation of ASEAN member states in the bloc’s ASEAN Single Window, designed to enable electronic exchange of trade documents such as certificates of origin and customs declarations.

Inevitably, though, the pandemic also demonstrated the limitations of what is reasonable to expect of ASEAN in such a crisis.

In May of 2020, in the still early stages of the pandemic, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) thought it detected some “increasing policy convergence” in responses to the pandemic, driven by the high tempo of meetings and collaboration. This is hard to see in retrospect, except in agreement at a high-level on the kinds of policy measures that could help contain the pandemic and support economic recovery.

In practice, Southeast Asia resembled the rest of the world – even the European Union, with its much stronger tolerance of supranationalism – with significant variations in the “strictness” of border closures and lock-downs and other public health restrictions.

National governments led, and national circumstances dominated decision-making. Performance in containing the pandemic varied. So too did the extent and nature of fiscal measures to support those in most economic need. True convergence is only now emerging, as Southeast Asian countries shift to living with the pandemic and progressively open their countries and international borders.

National responses also led the scramble for vaccines in 2020 when these were in short supply and monopolised by wealthy countries. Scarred by that experience, few, if any Southeast Asian countries would want to rely on pooled arrangements for vaccine supply, although the COVID-19 response fund is now being used to collectively purchase vaccines on a modest scale.

Elsewhere, ASEAN’s attempts to forge an ASEAN “travel corridor” to support business travel during the pandemic came to naught. As Joanne Lin writes, the travel corridor framework envisioned a clunky “noodle bowl” of bilateral protocols rather than a single, ASEAN-wide approach. These discussions were still going in circles when ASEAN nations, bolstered by relatively high vaccination rates and the imperative of shifting to a “live with COVID” mode, began unilaterally opening borders.

And for all the support for free trade, there is little evidence that ASEAN members are using the pandemic to propel liberalisation beyond goods trade, especially in services and the cross-border movement of labour. Here, ASEAN’s vision of an economic community remains very much a work in progress and the pandemic a missed opportunity to break new ground.

The ASEAN report card is therefore mixed, but creditable given the severity of the crisis and the inevitability that national considerations would drive policy responses. The pandemic has not weakened ASEAN regionalism. Still, the real test of ASEAN’s COVID cooperation will come only when the next pandemic strikes. ASEAN will be judged more harshly on the record of the past two years if its new public health architecture fails to better prepare the region for the next crisis.

Skip to section:

InterviewSkip to section:

Interview