The Political Implications of Thailand’s COVID Crisis

By Craig Keating

Published on 26th August 2021

Read in 6 minutes

Political activist in Bangkok. PixHound / AdobeStock

Thailand’s worsening COVID outbreak has all but totally eroded the confidence of Thais in their government. It has also given the mostly young people who have been protesting on-and-off for more than one year against Prime Minister (and 2014 coup leader) Prayuth Chan-ocha yet another compelling argument for his ouster.

Still, despite frictions within the government, the pandemic is unlikely to ease his regime’s grip on power any time soon. But, by exposing the inability of Thailand’s traditional patron-client politics to protect lives and livelihoods, it will hasten nascent demands for more equality in Thai personal and political relations, with potentially profound longer-term implications.

Skip to section:

Death and danger as Delta gets away Protests not making headway Election unlikely Coup unlikely A cultural shift About the AuthorDeath and danger as Delta gets away

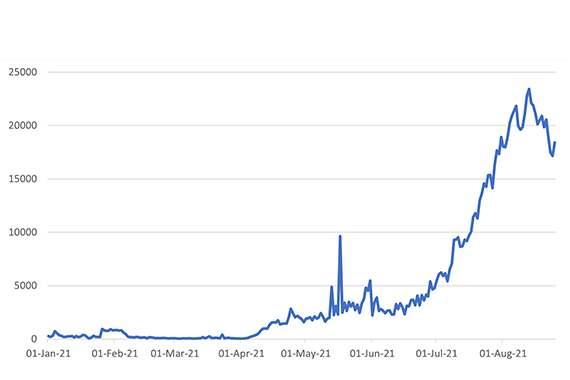

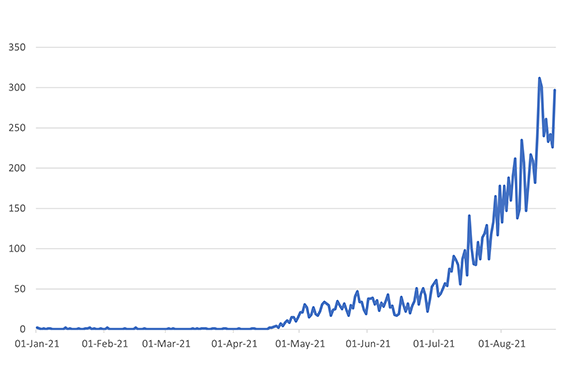

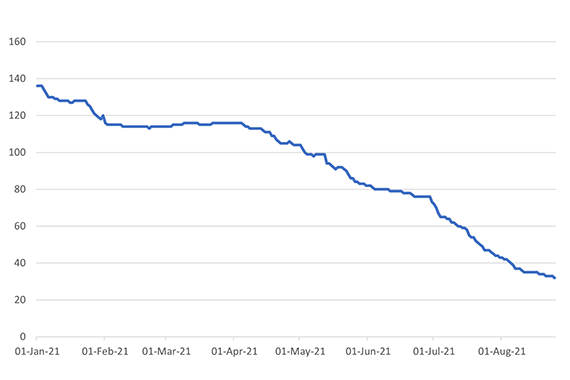

After Thailand’s initial success managing the pandemic last year, its daily infection (Graph 1) and death (Graph 2) rates have risen rapidly, although there are early signs that the peak may have passed. On 20 August, the country passed the sad milestone of one million cases since the start of the pandemic. The government’s complacency, including its failing vaccine strategy, left Thailand unprepared for the arrival in early April of the highly contagious Delta variant, and this has cost the Thai people dearly.

Graph 1: Daily reported COVID-19 cases in Thailand

Sources: Daily media reporting of Public Health Ministry figures.

Graph 2: Daily deaths attributed to COVID-19

Sources: Daily media reporting of Public Health Ministry figures.

Unsurprisingly, polling indicates most Thais are worried about the pandemic. Less than two per cent are confident the government will manage the crisis. They won’t be assuaged by Prayuth’s recent claim that Thailand is faring better than several other countries. Since the start of 2021, Thailand’s international ranking in terms of COVID performance has plummeted (Graph 3). And the proportion of fully vaccinated Thais falls well below that of several other Association of Southeast Asian Nation (ASEAN) members with far lower per capita GDP (Table).

Graph 3: Thailand’s COVID-19 international ranking (higher is better)

Sources: Daily media reporting of Public Health Ministry figures; Worldometers.

Table: Per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and vaccination rates in ASEAN

| Country | GDP per capita in 2020 (current $US) | Country | Proportion of population fully vaccinated |

| 1. Singapore | 59,797.80 | 1. Singapore | 74% |

| 2. Brunei | 27,466.30 | 2. Cambodia | 47% |

| 3. Malaysia | 10,401.80 | 3. Malaysia | 41% |

| 4. Thailand | 7,189.00 | 4. Brunei | 15% |

| 5. Indonesia | 3,869.60 | 5. Laos | 14% |

| 6. Philippines | 3,298.80 | 7. Indonesia | 12% |

| 7. Vietnam | 2,785.70 | 6. Philippines | 11% |

| 8. Laos | 2,630.20 | 8. Thailand | 8% |

| 9. Cambodia | 1,512.70 | 10. Myanmar | 3% |

| 10. Myanmar | 1,400.20 | 9. Vietnam | 2% |

Sources: World Development Indicators, Our World in Data – as of 23 August 2021

Protests not making headway

The current round of largely youthful protests in Bangkok are unlikely to unseat the government because the disparate groups involved are not united on much apart from wanting Prayuth to step down.

As the Covid crisis has worsened, some demonstrators have called for the government to provide more effective vaccines. However, others have not resiled from their demands for more radical royal reform. Their use of provocative props, such as a guillotine, and tolerance to date of increasingly violent actions deters support from other opponents of the government.

The major opposition parties are staying well clear. And those veteran activists who have taken to the streets have made sure they’re keeping a good distance, too. Until the young protesters renounce violence and put on hold their more provocative calls for royal change, they won’t attract mass support.

An opposition law suit against the prime minister over his handling of the pandemic is unlikely to succeed. Even in the remote chance that it costs Prayuth the premiership, he would likely be replaced by another party nominee from the junta-backed Palang Pracharath Party. Probably the most that opposition parties can hope for is that the case will embarrass Prayuth, and cost him yet more political capital.

Election unlikely

In the middle of a pandemic, an election is the last thing most Thais would want—and not only because of the health risks associated with a campaign. They know that the political system has been rigged to thwart the return of a popularly-elected government.

Despite being under pressure, Prayuth continues to hold many political cards—a constitution engineered to present a democratic veneer to his continued, unelected, leadership; a handpicked senate; and compliant election commissioners. His opponents have to change this political system—a Herculean task—before they would have a realistic chance of ousting him or any replacement that he might nominate.

That said, the two biggest parties in the coalition government are trading barbs over who is to blame for the vaccine debacle. But both have much to lose were the government to dissolve in the next few months. Their reputations (and electoral support) are tied to the two big issues facing Thailand — COVID-19, and its economic consequences. So this infighting probably won’t be a serious threat to coalition unity until and unless the COVID situation improves and the economy is recovering.

Coup unlikely

Nor is the government likely to be unseated in a coup in coming months. Coup planning is perhaps the only well-kept secret in Thailand — even many palace intrigues manage to find their way surreptitiously to political commentators.

A coup today would be more problematic for the palace and the military than it was in the late King Bhumibol’s time. In every coup since 1957, after the military seized power, the coup leaders were excused by King Bhumibol — to the extent that, in the words of Police General Vasit Dejkunjorn (who served in the king’s security detail), it had become “customary”. Both parties benefitted from this arrangement. The military received palace sanction for seizing power, and the palace was not involved overtly.

This ambiguity is no longer possible. In October 2019, the government ceded control to King Bhumibol’s successor, Vajiralongkorn, of key army units in Bangkok. Historically these units have been central to any successful putsch.

So, a future coup would either have the king’s clear blessing or direction, or it would be a move by the army against the palace.

The former would be seen as an overt royal intervention in politics, and leave many Thais holding the king responsible for any adverse fallout. And the latter would reduce the prestige and authority of the crown and, even more importantly, deny the military any royal legitimacy.

A cultural shift

Rather than a dramatic and immediate shake up of politics, Thailand’s COVID crisis will likely give greater impetus to nascent changes to Thai cultural values that, if realised, could see fundamental transformations in Thai political dynamics over the course of a generation.

Although Thailand overthrew its absolute monarchy in a 1932 coup, it has yet to make a full transition to democracy. Further, its politics have in the main been governed by principles of patronage and clique-building, which have fitted Thai hierarchical cultural norms, and also underpinned the monarchy’s claim to the apex position in Thai society.

Almost without exception, parties are controlled by a family or individual who, if not overtly leading the party, chooses the party’s titular head. The de facto party head would promise rewards to cliques—a group of politicians led by a powerful and wealthy person—which they hoped would win enough seats for their party to get into government. The more the electable politicians in a clique, the greater its value. Many politicians would shop around parties to get the best deal. Some politicians almost made it into an art form.

Rally in Thailand – Pratchatai – Flickr

But an increasing number of Thais are rejecting these traditional patron-client relationships. In the 2019 general election, 6.3 million Thais voted for a new party — Future Forward — putting it in third place. Its leader promoted equality and campaigned for an end to customs perpetuating traditional hierarchy. The party promoted a diverse Thai identity embracing ethnic minorities and cultural diversity. This was in stark contrast with the central Thai model to which all had been expected to conform since the 1930s. Free from the control of political cliques, Future Forward had in its ranks prominent academics, pro-democracy activists, and representatives of marginalised groups.

Some young protest leaders also want change. One defined their calls for palace reforms, including ending royal endorsement of coups and use of extra-legal authority, as a demand for “equality”.

The COVID crisis won’t change things overnight. Many Thais are comfortable within the traditional social hierarchy, and tend to tolerate the misuse of power. Polling from 2007 to 2013 showed two-thirds of respondents accepted corrupt government, if they also benefited. And local elections in December 2020 showed that patron-client politics still rule at the local level, where personal relations count more. So many will continue to vote for parties which deliver on promises to put money in their pockets, even after these parties are disrupted by coup or questionable court rulings.

That said, the unexpected level of support for the Future Forward Party in 2019 shows that political parties can succeed at the national level without needing to rely on traditional patronage networks. Space appears to be opening for issues- and values-based parties in Thailand. And this will likely only increase as demographic change gives greater weight to the voices of Thailand’s younger generation.

So change will take time, but time is on the side of the young.

About the Author

Craig Keating is a former senior analyst with Australia’s Office of National Assessments (ONA). Prior to joining ONA, he held numerous positions with the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID).