Bringing Back the Everyday Days: How Young Southeast Asians Coped with Life in Limbo During the Pandemic

By Various Artists

Published on 24th June 2022

Read in 11 minutes

Young people have been some of the hardest hit during the pandemic. With several formative years stolen by COVID-19, our education has been uncertain, social lives constrained, and career aspirations delayed or destroyed. Yet despite its heavy toll on us, we have had little power or influence over how our communities address the pandemic and its resounding impacts.

While there are many articles that detail the effects of COVID-19 on youth, these facts and figures often fail to reveal the real accounts and important details that make up the true experiences of those who have lived through it.

We start to fill that gap by giving a voice to young people throughout Southeast Asia. We asked them to tell us their stories. The result is a powerful series of personal reflections, some told through text, others through photographs, and yet others through art pieces.

Young people across Southeast Asia and beyond have shown incredible resilience as they face the ramifications presented by the pandemic, coupled with pre-existing challenges relating to poverty, inequality, political instability, lack of employment and educational opportunities and conflict. We are proud to showcase some of this strength.

This project is still open to submissions. If you would like to be involved please contact megehocking@gmail.com and moeayeayemyint108@gmail.com for more information.

Meg Hocking and Moe Aye Aye Myint

Skip to section:

Alessi (25, Philippines) Aung Chan Myae (21, Myanmar) Dave Pantoja (25, Philippines) Suthida Chang (26, Thailand) Arianna (29, Philippines) Glenn M. Vasquez Jr. (21, Philippines) Nurul Nadiah Binti Ali (23, Malaysia) Jazmin Wright (20, Vietnam)Alessi (25, Philippines)

Age: 25

Country: Philippines

Instagram: @byhervision_

VSCO: https://vsco.co/portraitsbyalessi/gallery

About a year ago someone asked, how Covid changed my photography. I am still fascinated by that question and I am still without a proper answer.

As to me, there’s a lot of emotions I put into my pictures. Like observing a dismantling point of view as you have no chance to escape that uncommon context on one side and using filters on the other side, that bring back the everyday days, remembering a world with less restrictions, a planet without a pandemic, a state of affairs when most travelled freely, and a time when the world as it is today was inconceivable. It´s inspiring unanswered and in the midst of pandemic, we all have questions that remained unanswered however, I took it as a chance to look forward and somehow seek the truth, the truth that cannot be changed and there I found the Word of God. My faith grew stronger as I have reflected in what was happening in the world and yes, I got two tools to remain sane in those times, the Bible and my camera.

Aung Chan Myae (21, Myanmar)

Age: 21

Country: Myanmar

Instagram: @typical.pixa

Aung Chan Myae describes his experience of the Covid-19 pandemic as “really tiring and depressing.”

The outbreak started in Myanmar in February 2020. Schools and offices closed, as the government announced a lockdown. Months later, Aung Chan Myae’s whole family were infected by the virus.

“I even lost my siblings and grandma because of Covid,” he says.

Infected himself, Aung Chan Myae spent two months in a quarantine centre.

“Everyday I coughed a lot, experienced headaches and I couldn’t breathe well and barely talked.”

He describes the outbreak’s third wave as “the worst thing [he] had ever encountered in [his] life.”

“Every single day around 500 people died. Even at the cemetery there were piles of dead bodies. It was like an apocalypse. Everyone encountered losses of their beloved people.”

Aung Chan Myae says the pandemic “changed [his] life completely.” It derailed his financial security, friendships, hobbies and education. Despite the hardship Aung Chan Myae has faced during the pandemic he remains amazingly positive.

“From my story, what I really want to tell people is not to give up. Keep chasing your dreams and don’t let things stop you from moving on. Be brave, be strong and believe in yourself. And never stop learning.”

Today, back to his health, Aung Chan Myae has started his own small business, is studying art at university and has met new friends online from all around the world.

Dave Pantoja (25, Philippines)

Age: 25

Country: Philippines

Instagram: @dave.pantoja

Dave shares his experience of living through the pandemic in Melbourne, Australia. Footage depicts his apartment, the Queen Vic Market, local cafes and Docklands, all places he ventured during this time.

Suthida Chang (26, Thailand)

Age: 26

Country: Thailand

Instagram: @one_purple_polar_bear

Mirror Mirror

I’m a classic ‘Third Culture Kid’ born in Thailand and grew up across Bangkok, Beijing and Singapore. Growing up, I’ve been inundated with stereotypes about how women should act and what type of person I should become in order to ‘bring honor to the family’. Because of my background and being ever-so-curious, I picked up pieces of my personality from different places — which became a bit of an identity crisis. At the height of COVID-19, I temporarily moved to London to complete my masters. It was an eye-opening experience — good and bad — that pushed me to rethink my relationship with the world around me. I’ve realized that no matter how horrible things can get and how nasty people may be, do not ever doubt your worth. Stay grounded and fight for your voice to be heard!

Arianna (29, Philippines)

Age: 29

Country: Philippines

Instagram: @arianna_lim

As a temporary visa-holder, being in Australia at the height of the pandemic was both fortunate and incredibly taxing.

The border closures that shut most immigrants out meant that if I left the country—either to go home to my family in the Philippines or to be with my then-partner in America—it would have to be permanently.

Encouraged by family to stay, I spent Melbourne’s long lockdowns (and their brief intermissions) taking photos. I walked for hours through areas I’d lived in for years but had never really taken in.

The photos I’ve shared here are from that period, when I seesawed between conflicting sentiments:

Guilt, for experiencing a Covid response that was infinitely better coordinated and humane than that of the Philippines, where for a while even leaving your house for a walk was prohibited.

Flowing on from that was my frustration with Australians’ misery at being locked down, which I recognise was misplaced and unfair.

But also—and what I hope comes across through this project—joy, from capturing a side of Melbourne I never would have seen otherwise.

Glenn M. Vasquez Jr. (21, Philippines)

Age: 21

Country: Philippines

Instagram: @steedles.embroidery

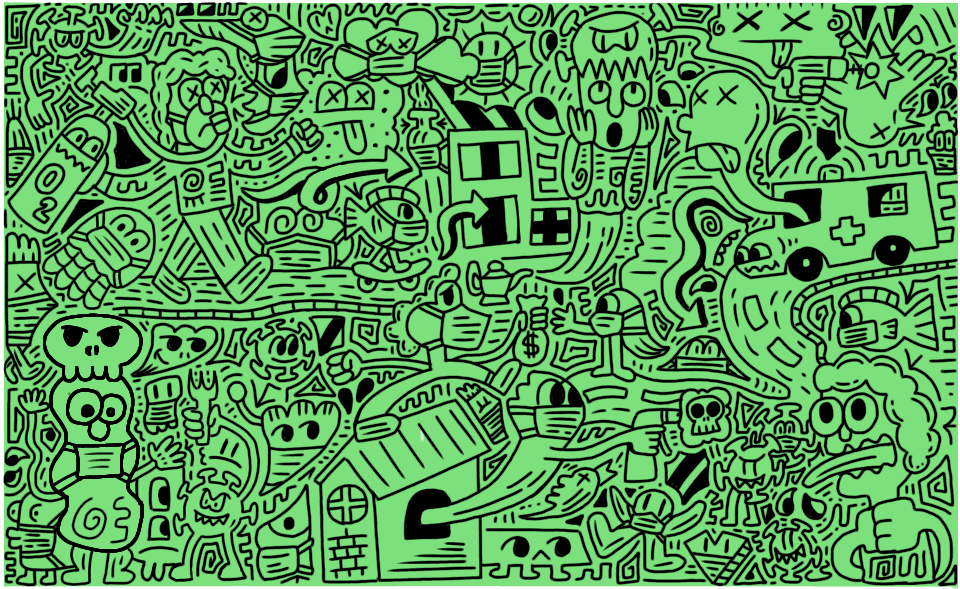

Disentangled Connections

To say that Filipinos are sociable people would be an understatement. From karaokes and group studies to casual hangouts, we always find a reason to get together. This piece is based on a picture of my classmates and me in 2019, enjoying what we didn’t realize would be our last Christmas event at university.

Like threads that are disentangled from a well-crafted embroidery, the pandemic has caused connections- real-time human connections, to be stripped away from us.

Nurul Nadiah Binti Ali (23, Malaysia)

Age: 23

Country: Malaysia

Instagram: @aalysya_widya

Jazmin Wright (20, Vietnam)

Age: 20

Country: Vietnam

LinkedIn: Jazmin Wright

The start of a new decade normally brings prosperity and excitement, with the ‘new year, new me’ mentality in full force. 2020 was supposed to be the year of new beginnings for me, as I was starting my studies at university and ready to explore the world as a young adult. Instead, 2020 was the year the world completely changed for everyone. The Covid-19 pandemic brought the world to a halt and tested people on an individual and community level. Reflecting on my pandemic experience, it’s hard for me to speak positively – and this was the sentiment shared by many of those around me. When hearing the word ‘Covid-19’, people think about lockdowns and vaccine mandates, but when I think of it, I think of loneliness and Asian hate.

I, like many other students who studied during the pandemic, suffered greatly from limited social connections at university and remote-study loneliness. In my second year, I started to meet people in my degree, but it was in my third (and final) year that I formed a solid group of friends in my studies – simply because nearly half of my degree was virtual. Making friends via Zoom classes is challenging and awkward, but it always felt that my peers and I bonded in the break-out rooms through discussions about the social and academic struggles of studying remotely. As terrible as it is, it was reassuring to hear others also struggle, as I know that I’m not the only one feeling that way.

While more generally, isolation and loneliness were common themes throughout the pandemic and brought unprecedented times for many. People lost their jobs or were forced to work from home, students had to study remotely, and social groups were suspended. The drastic severing of in-person social connections throughout the pandemic took its toll, with Covid-19 testing individuals’ resilience and their ability to persevere during a time of collective despair. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, almost 25 million Medicare Benefits Schedule-subsidised mental health-related services were processed between March 2020 and January 2022. While this figure is significant, it does not account for those who did not seek help throughout the pandemic or sought out alternative means for support.

Frustration and fear were also common sentiments, particularly for diasporic Asians living in the West. It wasn’t necessarily out of concerns for contracting the virus, rather, the hate towards Asians associated with Covid-19. The pandemic exposed two things. Firstly, in the eyes of the public, Asians are monolithic, meaning that the public fail to recognise the differences between Asian cultures and perpetuates the idea that all Asians are the same. Many people blamed both East and Southeast Asians for Covid-19, solely based on appearances and stereotypes. I remember when I was waiting for a train during the early days of the pandemic, and this older man came up to me and told me that “people like me are the reason why the world is suffering”, “to go back to where I came from”, and to “stop spreading the virus”. In that moment, my Australian-Vietnamese identity did not matter. To them, I was just another Asian.

Secondly, the pandemic demonstrated that hate towards Asians is normalised. While the online world served as the perfect vessel to keep everyone connected during the pandemic, it also acted to spread misinformation about Covid-19 and hate towards East and Southeast Asians. Stigmas around Asian food were reinforced, with jokes about eating bats and dogs rampant and people avoiding Asian food altogether, all because they don’t want to catch the ‘Asian flu’. According to a L1GHT report, there was a 200% increase in traffic to hate sites and posts against Asians online, which helped to fuel physical hate crimes towards Asians. Constantly hearing stories of racially motivated violence was challenging, which furthered isolation and negativity I was already experiencing during the pandemic. In my eyes, people’s negative attitudes towards East and Southeast Asians that spurred from Covid-19 reversed several years of acceptances and strides to create cross-cultural understanding.

While the pandemic was not all doom-and-gloom – I think there were some valuable lessons that were presented during this time. As a society, we were forced to have critical discussions of mental health, while on an individual level, we were encouraged to find balance and take measures to improve wellbeing. As a young student, I learnt how to become more resilient and how to adapt to unideal situations. In saying this, loneliness and isolation, the stories of other East and Southeast Asians, and the racism I faced as a young Australian-Vietnamese woman, made my Covid-19 experience miserable and negative.