The Pandemic and the People: Southeast Asian Attitudes to COVID-19 Responses

By Eve Warburton

Published on 12th August 2021

Read in 2 minutes

BMA officer addressing people at a Bangkok testing centre. Adirach Toumlamoon/Shutterstock

New research on Southeast Asian public attitudes of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic has been conducted by a team of researchers from Australia, Asia and the United States.

The paper ‘COVID-19 in Southeast Asia: Public health, social impacts, and political attitudes’ is based on online survey results from over six thousand respondents in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines. The study, by researchers Edward Aspinall, Nicole Curato, Diego Fossati, Eve Warburton, and Meredith L. Weiss, is part of a larger project funded by Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade – Supporting the Rules-Based Order in Southeast Asia (SEARBO).

The survey was conducted between mid-April and late-May 2021 and featured 66 questions about the pandemic experience, including views on government response to the pandemic, health and economic impacts, concerns about crime and personal rights, and more.

Dr Eve Warburton explains that a significant focus of the research explored whether citizens of Southeast Asian nations are accepting of, or even demanding, stronger state interventions from their governments.

“The sorts of illiberal interventions that we know elites are introducing all around the region – are citizens agreeing with them? Is this what they want?” she says.

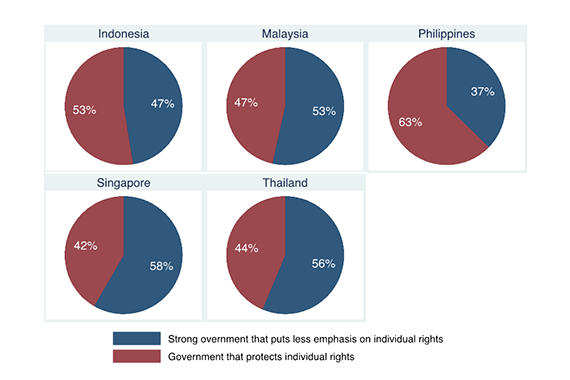

When asked about government interventions, based on real-life scenarios, the survey results found “in the broader sense a lot of people in Southeast Asia would prefer strong government intervention with less emphasis on individual rights.”

Preferences over individual rights, by country

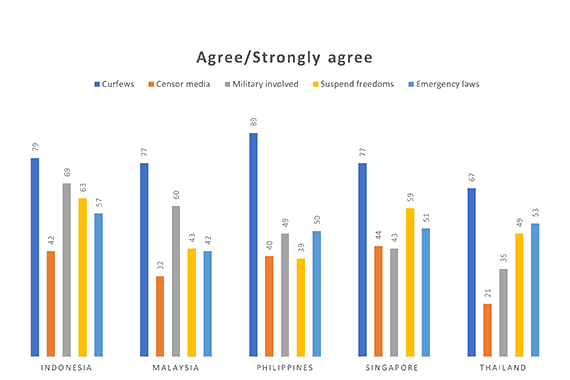

In a proposed hypothetical scenario where the pandemic worsened, the survey found “really, really strong support” for curfews, and “majority support, although sometimes a slim majority” for executive government introducing emergency decrees without parliamentary support.

The survey found much variation when it came to support for suspension of civil liberties. In Indonesia, 63 per cent of respondents agreed that if the pandemic got worse the government should be able to constrain civil liberties, but only 43 per cent of Filipinos agreed.

Across all the countries surveyed, the research found what Dr Warburton describes as an “illiberalism threshold”. A majority of respondents in all countries disagreed that the government should be able to censor the media – something that is already occurring in countries around the region, including Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia.

“We’ve seen governments introduce measures against ‘fake news’ and misinformation that are really an attempt by the state to exert control over the media.”

There was strong support in Indonesia – “our most democratic country” – for involving the military in government in the context of a pandemic emergency, with 63 per cent in favour. The lowest rate of support comes from “our least democratic country” Thailand, at just 35 per cent.

Support for emergency measures, by country

“Indonesians, in our sample, came out as the most willing, on average, to accept all of these measures” Dr Warburton reveals.

“One takeaway is that it doesn’t bode well, in terms of the extent to which we might find public resistance to trends of democratic decline,” she notes, “in Indonesia specifically, where we know that this has been happening for a number of years now.” (see also: COVID-19, Government and Security in Southeast Asia).

The survey also covered varied national impressions of the health versus economic impact, the increased pressure on women, and vaccine hesitancy, and Dr Warburton discusses how the results might have been different in the face of the Delta variant.

Interview

About the speaker

Dr Eve Warburton is a postdoctoral fellow at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Eve received her PhD in 2018 from the Australian National University’s Coral Bell School of Asia and Pacific Affairs. Her doctoral dissertation examined the political economy of resource nationalism, and in particular the role that domestic firms play in shaping nationalist policy trajectories.

She is now finalising a book manuscript based on her dissertation, Reclaiming What’s Ours: A Political Economy of Resource Nationalism in Indonesia.