Chinese Digital Diplomacy in Southeast Asia During the Pandemic

By Fangyuan Huo and Richard Maude

Published on 21st September 2021

Read in 16 minutes

In recent years, especially from 2018, Chinese embassies and senior diplomats have taken to Twitter and Facebook in growing numbers.

President Xi Jinping wants his diplomats to tell China’s story well – to build China’s global influence, guard the “truth” and correct “misunderstandings”. Public diplomacy is presented as another battlefield on which China must win.

Xi also wants a foreign ministry with “guts”, willing and able to assert China’s national interests forcibly, defend its dignity and remind the world that it must deal with the realities of China’s contemporary power.

Twitter and Facebook (platforms banned in China) are just one part of a broad suite of public diplomacy tools used by China. But they attract considerable attention, because of their reach in many countries and their ability to be used for disinformation.

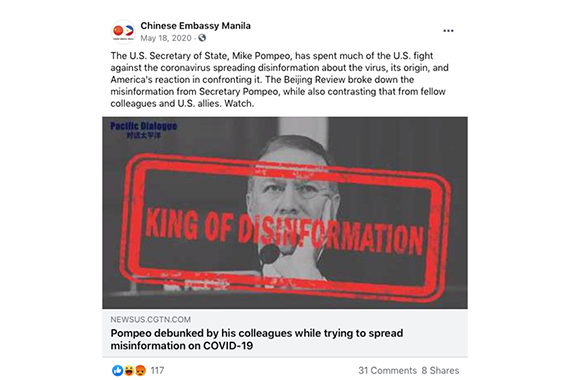

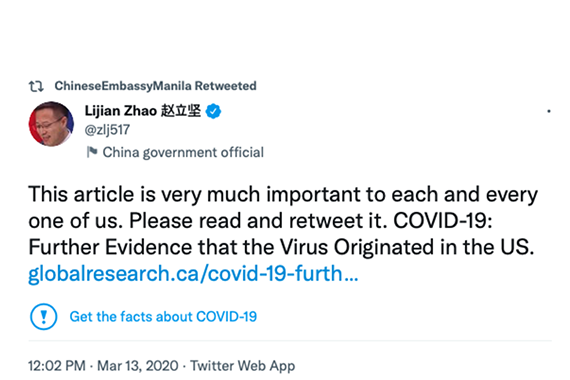

Several studies have found that China has adopted Russian-style propaganda tools, including the use of trolls and bots to maximise social media coverage. Senior diplomats also “amplify spin and outright false messages”, such as on the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Southeast Asia, a region with young and digitally connected populations, social media platforms are now established public diplomacy tools for China’s diplomats. But it is Facebook (11 accounts) rather than Twitter (two accounts) that dominates (see table below),

We sampled the digital diplomacy activities of four of these accounts over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic: the Twitter accounts of the embassy to the Philippines and Ambassador to ASEAN, and the Facebook accounts of the embassy to Thailand and the embassy to Vietnam.

We find that Twitter and Facebook are used in Southeast Asia by Chinese diplomats at least in part in ways similar to their counterparts from other countries. For example, they promote human interest and cultural stories from China, post records of meeting with local officials, and highlight China’s trade and investment links to Southeast Asia.

Messages of direct relevance to local audiences are generally kept positive in tone, with a heavy emphasis on China as a supportive partner – especially in Southeast Asia’s moment of pandemic need – and a responsible global power.

With some exceptions in the Philippines, we did not identify any social media posts directly targeting Southeast Asian political leaders or public opinion makers with the type of inflammatory “wolf warrior” style diplomacy seen in other parts of the world. Chinese diplomats in Southeast Asia likely judge that this would be counterproductive, nor would they usually see much need to depart from positive messaging that would resonate with local audiences.

Some messaging, for example on the South China Sea, is specifically tailored to regional audiences, with a narrative of China working closely with claimant states to “maintain stability” while “outsiders” cause trouble.

In addition to digital diplomacy aimed at building positive influence for China in Southeast Asia, the accounts we sampled posted heavily in line with China’s global campaigns on issues such as the virtues of Communist Party rule, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, the origins of the pandemic, and China’s competition with the United States.

These posts almost always use text and images derived from Chinese government and state media sources. Following Beijing’s lead, the four accounts we examined promote conspiracy theories and disinformation, highlight US and western flaws and “hypocrisy” (over human rights, for example), and try to swamp negative coverage with glossy “positive” propaganda campaigns.

Digital diplomacy is only one element of Beijing’s broad-ranging and well-resourced efforts to build influence and shape and control global public narratives about China. But in Southeast Asia, growing influence does not appear to translate into growing trust.

Skip to section:

China’s Twitter and Facebook accounts in Southeast Asia “If you do not speak up, you will be criticised”: Chinese diplomatic Twitter in Southeast Asia Facebook vs Twitter: China’s Embassies in Thailand and Vietnam The impact of China’s digital diplomacy About the authorsChina’s Twitter and Facebook accounts in Southeast Asia

Data from February 2020 to May 2021, calculated on the dates indicated (see note below)

| Account | Language of posts | Followers | Interactions |

| Ambassador to ASEAN @China2ASEAN |

English | 42.9K | Average likes 35 Most liked 1,522 (numbers as at 3 June 2021) |

| Chinese Embassy Manila @Chinaembmanila |

English | 13.3K | Average likes 6.4 Most liked 920 (numbers as at 3 June 2021) |

| Chinese Embassy Bangkok @ChineseEmbassyinBangkok |

Thai Some English |

69K | Average likes and loves combined – 581 Most liked and loved – 23,032 (numbers as at 8 September 2021) |

| Chinese Embassy Hanoi @ChineseEmbassyinHanoi |

Vietnamese Chinese |

37K | Average likes and loves combined – 101 Most liked and loves combined – 5,112 (numbers as at 11 August 2021) |

| Chinese Embassy Manila @ChinaEmbassyManila |

English | 124k | |

| Ambassador to the Philippines @AmbHuangXilian |

English | 34k | |

| Chinese Embassy Singapore @Chinaemb.SG |

English Chinese |

92k | |

| Chinese Embassy Yangon @Paukphawfriendship |

Burmese | 226k | |

| Chinese Embassy Jakarta @ChineseEmbassyinIndonesia |

Indonesian | 5k | |

| Chinese Embassy Kuala Lumpur @Chinaembmy |

English | 72k | |

| Chinese Embassy Phnom Penh @ChineseEmbassyCambodia |

Khmer Chinese |

65k | |

| Chinese Embassy Brunei @Chinaembbn |

English | 424 | |

| Chinese Embassy Dili @embassyofchinaintimorleste |

English | 11k |

Note: Studies, such as this one on Chinese diplomatic Twitter accounts in Europe, show strong evidence of the use of bots in an attempt to amplify messages, for example by use of fake accounts to “like” posts. We have not undertaken similar data analytics here, but note that we experimented by testing on the Botometer a very small number of accounts that “liked” posts on the Twitter account of the Chinese Embassy in Manila and found accounts with scores indicating bot-like behaviour.

“If you do not speak up, you will be criticised”: Chinese diplomatic Twitter in Southeast Asia

From early 2020 through to July 2021, four themes were particularly prominent on China’s two diplomatic Twitter accounts in the region.

The Pandemic

Not surprisingly, the pandemic is a major focus of China’s digital diplomacy in Southeast Asia, with both “positive” (China’s pandemic aid) and “defensive” (origins of the pandemic, vaccine effectiveness) themes strongly evident.

China’s “responsible” performance in containing the pandemic in 2020 is repeatedly highlighted. With the pandemic under control in 2020 and Beijing looking outwards, posts emphasised the need for global action to fight the pandemic and China’s assistance to Southeast Asian countries, beginning with face masks and other personal protection equipment, and visits to some Southeast Asian countries by Chinese medical teams.

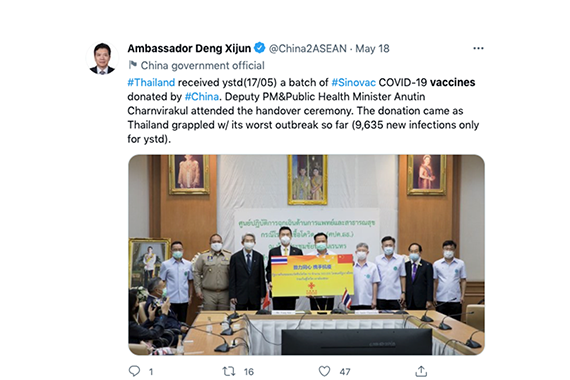

The progress in developing Chinese vaccines is tracked and, from December 2020 as China began to supply vaccines to Southeast Asian countries, multiple posts record this early assistance (which allowed many regional countries to kick start their vaccination programs).

A number of posts compare China’s management of the pandemic in 2020 and pandemic-related assistance with the Trump Administration’s “incompetent” response in the US and “hoarding” of vaccines.

Embassy posts highlight China’s Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine as the first non-Western vaccine to be given emergency approval by the World Health Organization (WHO). Posts also praise China’s efforts to make its vaccines accessible and affordable to developing countries, emphasising vaccine donations as much as commercial arrangements (China’s donated doses are small compared to China’s doses sold in Southeast Asia), and Beijing’s commitment to donate to the COVAX vaccines initiative.

China (as the Ambassador to ASEAN posted, quoting Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi) is portrayed as “builder of world peace, a contributor to global development … and a provider of public goods”.

In addition to this relatively routine public diplomacy promoting China’s support for Southeast Asia, both embassies took up broader global campaigns by China to muddy the waters on the origins of the pandemic, attack the US and others’ calls for greater transparency and an independent investigation, and defend the efficacy of Chinese vaccines.

Both Twitter accounts were used to re-post disinformation suggesting the pandemic might have originated in the United States or other countries. Other posts note the advantages of Chinese vaccines (e.g., not requiring extreme cold storage) and the “safety” benefits of inactive vaccines.

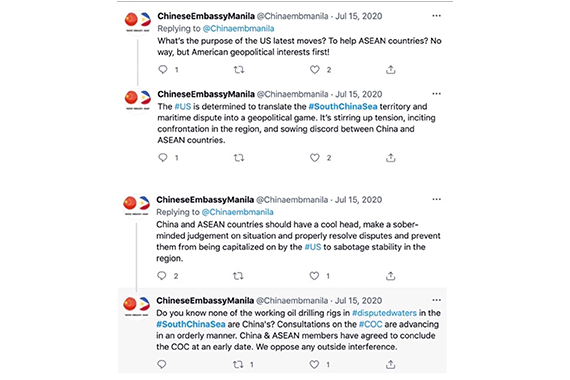

South China Sea

China’s extensive claims in the South China Sea – a source of tension in Sino-Southeast Asia relations and an arena for US-China rivalry – are another major theme of Beijing’s digital diplomacy on Twitter.

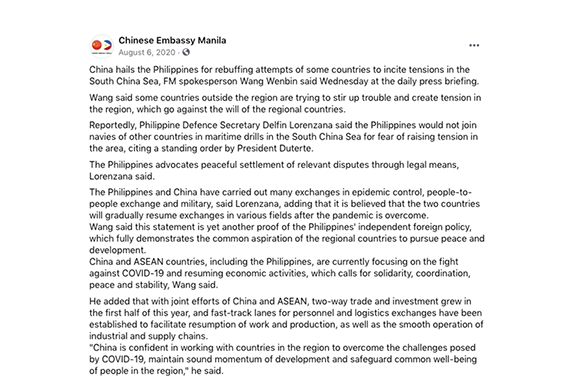

Posts portray the United States as the major source of instability and tension in the South China Sea and denounce Washington for inciting conflict between China and ASEAN countries in order to contain China. In contrast, China is portrayed as responsibly managing South China Sea issues and working jointly with regional countries to maintain stability.

Embassies work to co-opt Southeast Asian countries into China’s preferred narrative. For example, appealing to ASEAN countries not to be “used” by the United States, the Chinese Embassy of Manila praised the Philippines for “rebuffing attempts of some countries to incite tensions in the South China Sea” as the Philippines rejected an invitation to join the naval forces of other countries in maritime drills.

China’s narrative conveniently ignores, of course, the very evident concerns of many Southeast Asian countries with China’s pursuit of de-facto control of the South China Sea and its disregard for the 2016 UN Law of the Sea arbitral tribunal ruling that demolished any legal grounds for Beijing’s extensive maritime claims.

Human Rights

As allegations made by the United States and other Western countries regarding genocide, forced labour and internment camps in Xinjiang gained traction, Xinjiang also became a trending topic in Beijing’s Twitter diplomacy.

The two accounts we sampled cover Beijing’s “wonderful land” propaganda campaign, for example, which seeks to portray a “happy and prosperous” life in Xinjiang and promote China’s claims of supporting economic development, social stability and religious harmony (a campaign rolled out worldwide including – to much ridicule – in Australia).

Posts calling the “Uyghur genocide” as “the lie of the century” were tweeted or retweeted by Chinese embassies and ambassadors, condemning US-led “anti-China” forces for stirring up ethnic conflict in Xinjiang with the aim of containing China’s rise.

Posts also sought to discredit Western, especially US, criticism of China’s actions in Xinjiang by highlighting the United States’ own often poor human rights record at home and abroad.

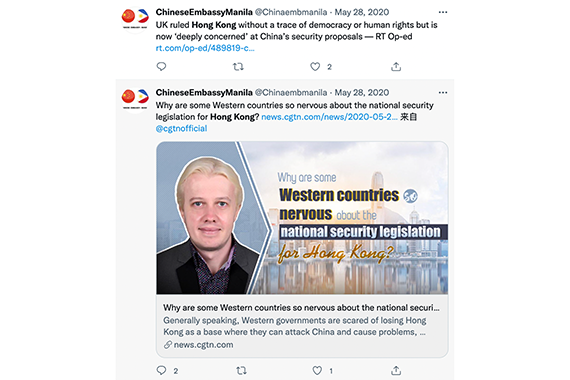

China is also seeking to discredit human rights concerns being voiced about Hong Kong, with posts condemning the UK for “grossly” interfering in Hong Kong affairs and urging the United States to “quit its old bad habit of hegemonism”. Such rhetoric is likely designed to appeal to regional nationalism and the lingering hostility of some in the region to perceived imperialism or neo-colonialism by the United States and other Western powers.

Flood of Positive China Narratives

Other content involves a flood of positive posts about China’s national achievements, such as its post-pandemic economic recovery, its carbon pledge, and its scientific and technological developments. Some highlights include:

- High profile praising of China’s “victory” against poverty (in February 2021, Xi Jinping announced China had ended “extreme poverty” in China)

- Branding China’s economic “miracle” and its long-term social stability as proof that the Chinese system, with the Communist Party at its centre, is robust and successful

- Emphasising Xi Jinping’s 2060 net zero emissions pledge and China’s commitment to becoming a global leader in clean energy

- Highlighting recent achievements in aerospace science, including China’s space station

Wolves are More Polite in Southeast Asia

While the two embassy Twitter accounts are littered with a flood of often aggressive material directed against the United States, we found no attacks on Southeast Asian political leaders comparable to the worst examples elsewhere of Chinese “wolf warrior” diplomacy.

This is unsurprising given the relatively stable relations between China and Southeast Asia, and the regional culture of delivering harder messages behind closed doors.

Still, the Chinese Embassy in Manila posted on its Twitter account a series of statements from the Embassy spokesperson that use language that in days past would have been seen as unusually sharp for diplomats, if not breaching the convention of non-interference in host government affairs.

On 22 April 2020, for example, the Embassy posted a statement saying that it was “ridiculously absurd and irresponsible” for Philippines Senator Risa Hontiveros to claim that China should pay for the Philippines’ COVID-19 response.

Similarly, in response to the presence of large numbers of Chinese maritime militia vessels in the Philippines EEZ in March and April 2021, the Embassy’s Twitter account carried a statement saying there was “no Chinese Maritime Militia” and that “any speculation in such helps nothing but causes unnecessary irritation”. The Embassy statement went on to hope “that the situation could be handled in an objective and rational manner”.

US allies and close partners are largely spared from campaigning by the two embassies, but the ASEAN Ambassador’s account includes a few re-posts blaming Australia for the collapse in relations with China, along with a lone post attacking the 2021 G7 foreign minister’s statement (“groundless accusations against China and wanton destruction of the norms of international relations”).

Several tweets re-post official Chinese government statements attacking Japan’s proposal to discharge treated water stored at the site of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor.

Facebook vs Twitter: China’s Embassies in Thailand and Vietnam

We sampled the Facebook pages of China’s embassies in Thailand and Vietnam over the same period (February-March 2020 through to July 2021) to compare them to the two Twitter accounts.

Material on the Facebook pages broadly covers the same themes identified above, although there were some differences, reflecting both specific country/relationship circumstances and the different nature of the platform.

China’s response to the pandemic receives extensive coverage on both pages.

Early posts (February-March 2020) on the Embassy to Thailand account are notable for how quickly China sought to steer Thailand and Southeast Asia away from any suggestion that allowing the pandemic to spread in the region threatened Southeast Asian lives and economies and towards Beijing’s preferred narrative of China standing with its neighbours in a shared battle in which China was showing the “highest responsibility”.

As early as 11 February 2020, for example, China’s Ambassador to Thailand was posting that “Thailand appreciates and supports China’s stance and action in the fight against the epidemic”.

China’s pandemic aid as a global “public good” is also given extensive coverage, including the arrival of Chinese vaccines in Thailand from February 2021 onwards.

There is somewhat less prominent coverage of bilateral COVID-19 pandemic aid on the Embassy to Vietnam’s Facebook page, likely reflecting Vietnam’s strong performance in 2020 in containing the pandemic together with the Vietnamese government’s reluctance to be seen domestically as relying on Chinese assistance.

Vietnam did not approve a Chinese vaccine for use until June 2021. The Embassy does record China’s subsequent donation of 500,000 doses of Sinopharm, which arrived on 21 June, and a smattering of posts record other assistance (such as face masks) over the period of review.

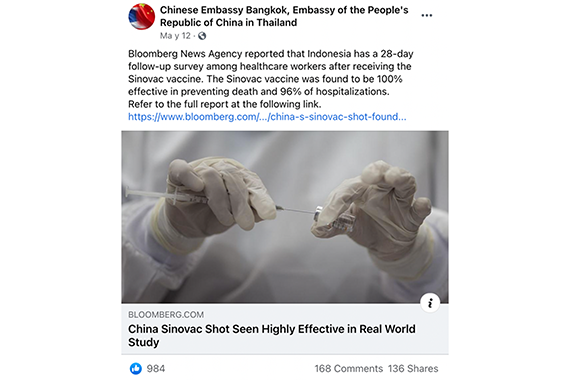

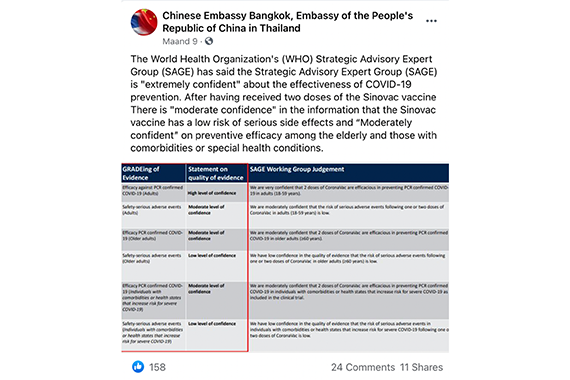

As the Delta variant began to ravage many Southeast Asian countries, the Embassy in Thailand responded to growing concerns about the effectiveness of the Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines with a flurry of posts through the period May-July 2021.

As with the two Twitter accounts, the United States is the main target of “negative” posts on both Facebook pages, especially during the Trump Administration.

A salvo of posts on the Embassy to Thailand account in March 2020, for example, attacked Trump Administration criticism of China’s management of the early stages of the pandemic (re-posted material from a range of sources, including official Chinese government statements), and a second mini campaign in July of 2021 re-posted material attacking suggestions the COVID-19 virus could have escaped from a Chinese laboratory.

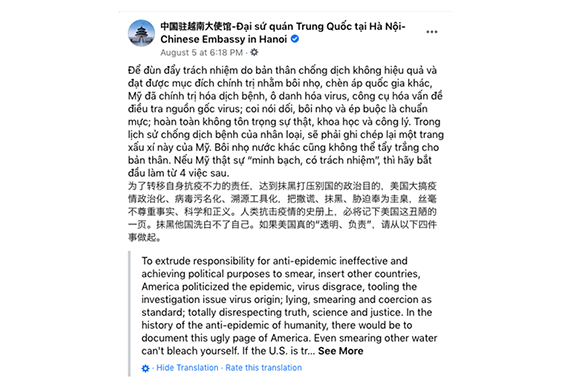

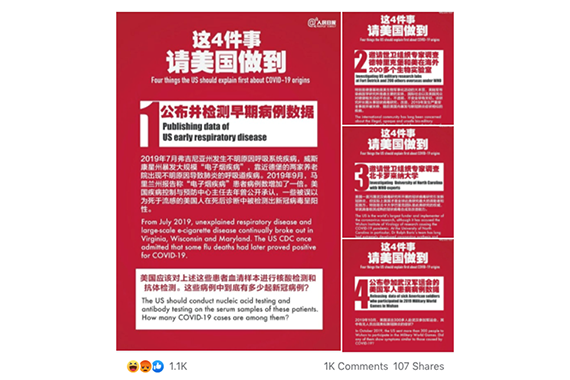

In a similar vein, the Embassy to Vietnam re-posted this graphic, which is based on comments made by Chinese spokesperson Zhao Lijian, on 30 July 2021.

Other material on both Facebook pages attacks the United States “lies” and policies on issues such as China’s security crackdown in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, along with the Trump Administration’s threat to ban Tik Tok and its closure of the Chinese consulate in Houston.

Even so, our overall impression was that both Facebook pages carried somewhat less highly-aggressive anti-US material than the two Twitter accounts, perhaps reflecting Twitter’s role as the primary vector of Chinese “wolf warrior” diplomacy, especially on hot-button issues where Beijing seeks to shape global debate on China.

Finally, we note some differences.

First, South China Sea issues receive relatively little attention, even on the Embassy to Vietnam account (Vietnam is a claimant state, Thailand is not). This was true of the Embassy of Vietnam’s Facebook page even at times of great tension between Vietnam and China on South China Sea issues. The 4 April 2020 sinking of a Vietnamese fishing boat after a clash with Chinese vessels, for example, is not mentioned.

Even Embassy statements attacking the United States for “hyping” risks in the South China Sea (amongst other perceived sins) posted on 24 November 2020 and 31 October 2020 are notable for refraining from any assertion of Chinese sovereignty. Rather, they emphasise the “clear consensus” China and Southeast Asian countries have reached to “jointly maintain peace and stability”. This ‘softly softly’ approach no doubt reflects the extreme sensitivity of competing South China Sea claims in Vietnam and the special nature of China’s relationship with Hanoi, especially its Party-to-Party ties. It is, though, a rare example of restraint on China’s “core” national interests when it comes to social media.

A rare break from this pattern in July 2020 immediately backfired. The journalist Dien Nguyen An Luong notes that a re-post by the Chinese embassy in Hanoi of a warning from Global Times editor Hu Xijin not to side with the United States to contain China created an immediate negative public reaction and the post was quickly taken down.

Second, unsurprisingly, China’s cooperation with Mekong countries, including through the China-centred Lancang-Mekong Cooperation forum, received wide coverage in Thailand and Vietnam. Both Embassies, particularly in Thailand, also posted material supporting China’s dam building on the Lancang (upper Mekong).

Third, also unsurprisingly, Party-to-Party ties are a prominent feature of the Embassy to Vietnam’s social media. Meetings between senior Party officials are recorded, Ho Chi Minh’s birthday celebrated, and Vietnam and China are hailed as “together opening a new chapter of socialism” (Asia Society translation).

Finally, Facebook’s video- and photograph-friendly format allowed both embassies to make full use of glossy, professionally produced campaign assets, both on political issues such as the Xinjiang and China’s success in alleviating poverty in rural areas (Thailand), along with material promoting China’s culture and natural beauty.

The impact of China’s digital diplomacy

A full analysis of the impact of China’s digital diplomacy in Southeast Asia – a task requiring detailed data analysis – is beyond the scope of this short paper. Here, we offer some general observations.

First, Facebook and Twitter allow China’s embassies to engage new audiences in Southeast Asia, albeit at modest scale given the size of most regional populations, and often with relatively limited interaction. The accounts we sampled are also often a platform for negative sentiment about China as much as they reflect appreciation for support like China’s pandemic aid.

Importantly, Twitter and Facebook provide a platform on which Chinese diplomats in Southeast Asia can follow Beijing’s lead in hitting back hard against critics and adversaries, especially the United States (“maintain a fighting spirit”, in President Xi Jinping’s words).

Second, China’s digital diplomacy sits within a much larger Chinese public diplomacy effort. China’s tool kit includes cultural and exchange programs, sponsored visits for elites, Confucius Institutes, scholarships programs and sister-city arrangements.

China has also invested heavily and strategically in recent years in its ability to shape and control global news and media narratives. China wants what the Communist Party calls discourse power, not just to tell China’s story well but, in the words of Foreign Minister Wang Yi, to “guide the international community to form a correct vision of China”.

Beijing builds influence and shapes perceptions of China in Southeast Asia through the use of Chinese state-owned media content in mainstream news sources, Chinese digital news apps, and news and opinion available on social media platforms like Facebook.

China has steadily built substantial ties to Southeast Asian media platforms – 2019 was the “ASEAN-China Year of Media Exchanges”. The state-owned radio and television broadcaster China Media Group hosts an “ASEAN Media Partners Forum”. A meeting in July 2021 attracted 33 media organisations from China and Southeast Asia.

News sharing arrangements support the regular use of Beijing-friendly state-owned media content in Southeast Asia. China’s playbook also includes advertising support, sponsored visits, and training for journalists.

Third, there is evidence that China’s concerted public diplomacy has paid some dividends in recent years.

A 2018 Asia Society report examining China’s public diplomacy in the broader region (East Asia and the Pacific), for example, found “some indications” that Beijing’s public diplomacy may be paying off in terms of more favourable public perceptions of China.

It also found “some evidence of a relationship” between China’s public diplomacy and votes by regional countries that backed China’s position in the UN General Assembly.

A recent study with a global scope found that Chinese public diplomacy on the pandemic, along with its medical assistance, to some extent offset the “reputational hit” China took over COVID-19, as measured by the tone of local media reporting. The report’s authors conclude that “it appears that Beijing’s health diplomacy charm offensive worked”.

Similarly, a 2020 global survey of affiliate unions of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) found that that China used the COVID-19 pandemic to boost its image in global media coverage. More than half of all countries said that coverage of China in their national media was more positive since the start of the pandemic.

Lastly, Beijing’s public diplomacy in Southeast Asia is also well-supported by China’s large trade and investment links, pandemic and other aid, institutional arrangements and its military power. These significant advantages have seen China’s overall influence in the region grow in recent years.

In sum, Beijing’s digital diplomacy in Southeast Asia is but one component of a determined, multi-faceted, well-resourced strategy for building influence and shaping perceptions of China.

Still, for all this, growing influence does not necessarily translate into trust.

The 2021 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) state of the region survey found that a majority of those surveyed (63 per cent) had either little or no confidence in China to “do the right thing” to contribute to global peace security and governance.

This is a significant increase from the 51.5 per cent of respondents who answered similarly in 2019.

The ISEAS survey captures elite views – “opinion-makers, policy-makers, and thought-leaders” – and suggests that, for this group at least, China’s public diplomacy in Southeast Asia is not easing concerns about its power, behaviour and future intentions.

About the authors

Fangyuan Huo is an Associate at Asia Society Australia. She is a recent masters graduate having completed a Master of International Relations at Australian National University. She has a strong interest in strategic relations in the Asia-Pacific region in the context of the US-China competition.

Richard Maude is Executive Director of Policy at Asia Society Australia and a Senior Fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute. Mr. Maude joined Asia Society after a 30-year career as an Australian diplomat and intelligence official. He is a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Director-General of the Office of National Assessments, and senior foreign policy adviser to Prime Minister Julia Gillard.