Southeast Asia’s Economic Outlook: New Variants Threaten Recovery

By Richard Maude

Published on 7th June 2021

Read in 11 minutes

Bangkok MRT – AdobeStock

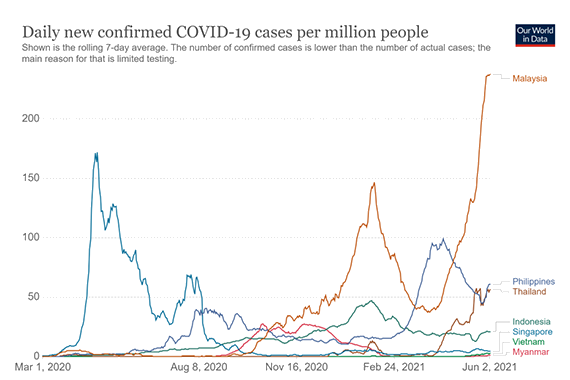

A surge of COVID-19 infections in Southeast Asia is costing lives and threatening to derail recovery from last year’s painful recession.

Except for Vietnam, which managed to keep growing in 2020, getting Southeast Asian economies back to health has been a slow and arduous process.

Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia, for example, were all still in negative territory in the first quarter of 2021, even if the rate at which their economies contracted was significantly slower than the dramatic plunges of the middle of 2020.

Higher levels of poverty and inequality, investment foregone, the loss of human capital and the cost of collapsing small businesses could take years more to overcome.

Still, in April the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecast a return to growth in most of Southeast Asia, helped by strong external demand for the region’s exports, accommodative monetary policy and government spending.

Importantly, Southeast Asia’s relatively successful performance in 2020 in containing the pandemic and re-opening economies underpinned the cautiously optimistic outlook for the year ahead.

That hopeful scenario is now seriously challenged by the pandemic’s resurgence.

The Indian and UK variants have a firm foothold and Vietnam recently reported a new hybrid of these two highly contagious strains.

Southeast Asian countries previously at the forefront of efforts to contain the virus are among those on the back foot.

Malaysia and Thailand, for example, are experiencing their most severe outbreaks yet, with record numbers of new infections and deaths being reported through mid-to-late May.

Even Vietnam and Singapore have been struggling to control small but stubborn new infection hot spots.

In Indonesia, the pandemic burns on, neither raging uncontrollably nor fading. But new cases spiked following the Idul Fitri holidays, worrying authorities.

And in Myanmar, the military’s disastrous grab for power has pushed the economy back down on its knees and smashed the public health system, leaving it more vulnerable than ever.

Southeast Asian governments are trying to ramp up vaccination programs but risk losing the race against time and proliferating new variants. There’s an urgent need for international assistance to boost vaccination supplies and help get economies on a sustainable recovery trajectory.

The Good

The big bright spot for some Southeast Asian economies has been the revival of external demand for their manufactured exports, especially medical supplies and the goods that households and companies have wanted while locked down or working remotely, like smartphones, computers and home entertainment devices. Component parts, like semi-conductors, have also been in strong demand.

Prices for Southeast Asian commodities, such as copper and palm oil, have also been strong: Indonesia has been a particular beneficiary.

The United States has been the primary driver of this external demand, as huge fiscal stimulus packages are pumped into the economy, but China and other big North Asian markets like Japan and the Republic of Korea have also been prominent.

Exports of electrical machinery and goods from Southeast Asia grew from $US380 billion in 2019 to $US406 billion in 2020, despite a drop in overall exports from the region in the same period of some $US29 billion[1].

This momentum has continued into 2021. Vietnam’s trade continues to boom – exports grew by 22 per cent to $US77.3 billion on a yearly basis in the first quarter, driven by demand for consumer goods like smartphones and computers.

Indonesian exports are growing again for the first time since the pandemic hit the region’s biggest economy, up nearly seven per cent in the first quarter of 2021.

Malaysia’s manufacturing output expanded by nearly seven per cent in the first quarter and Singapore reports similarly strong demand for electronic machinery and semiconductors and parts.

The relocation of some manufacturing to Southeast Asia, especially to Vietnam, prior to the pandemic has helped the region respond to surging demand for electronic products.

And, once it enters into force, the recently signed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) trade deal will give intra-Asian trade another boost.

General government balance as a percentage of GDP, change from the previous year. Source: Asian Development Bank’s Asian Development Outlook 2021

Government fiscal packages targeting individuals, households and businesses have also provided some much-needed support for the region’s economies, even if generally modest by advanced economy standings (see table above).

Finally, increased adoption of digital solutions across the region has been one positive effect of the pandemic. In Malaysia, for example, there has been a sharp increase in the number of businesses using e-commerce and digital payments.

The Bad

Even if Southeast Asian governments can defeat the new variants and keep their economies open, the region is likely to take a multi-speed path towards recovery.

Countries able to take advantage of the bounce back in global trade, like Vietnam, Malaysia and Singapore, should do better. In April, for example, the IMF forecast Vietnam and Malaysia to grow at better than six per cent this year.

Source: International Monetary Fund. ASEAN 5: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam

Source: Asian Development Bank’s Asian Development Outlook 2021

Others won’t do so well. Those economies less plugged into global manufacturing and trade, especially in electronics, will lag. Some countries have very limited fiscal space for further stimulus.

And the death of international tourism will continue to be a serious drag on several Southeast Asian economies.

Getting back to growth will only be the beginning of the recovery challenge.

For much of the region, positive GDP numbers later in the year won’t necessarily represent robust economic health: activity won’t need to be particularly strong to show a rebound when compared to last year’s lows.

Making up lost GDP growth could take years.

Poverty levels have increased. School closures and job losses could harm the future employment and income-earning potential of many Southeast Asians.

Women, especially the millions working in Southeast Asia’s informal sector and in tourism and service jobs, have been disproportionately affected.

Higher debt could limit new investment. Thousands of small businesses shut down in 2020: many will never re-open. ASEAN’s growing connectivity, especially the cross-border movement of people, has been significantly affected.

The World Bank estimates that unless this deeper damage is addressed, growth in East Asia and the Pacific (excluding China) could be as much as 1.8 percentage points lower than pre-COVID projections, even accounting for accelerating digitisation and the use of new technologies.

There are things Southeast Asian countries can do to help themselves: where there is the fiscal space, targeted ongoing support for households and businesses; keeping a weather eye on financial stability; and, pursuing productivity-raising investments, like improving access to high-speed broadband and investing in digitisation.

But the poorest Southeast Asian countries, like Timor-Leste, Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar (circumstances allowing), will need much more donor support. Without this, they could face what the IMF has described as a “great divergence” – faltering economic recoveries and a falling away of long-term economic growth, pushing even further into the distance convergence with wealthy economies.

The Ugly

After several years of steady economic growth averaging about six per cent, Myanmar managed to keep the worst of the pandemic at bay in 2020 and its economy still growing, albeit at a much lower 3.2 per cent.

This makes the tragedy of the military coup in February all the more bitter.

Protesters in Amarapura, Mandalay – Prachatai – Flickr

The wrecking ball Myanmar’s generals have sent through the country’s economy, which is forecast to contract by anywhere between 10 and 20 per cent in 2021, is truly extraordinary.

Military-led violence against civilians, investor caution and a determined civil disobedience movement have combined with the pandemic to deal a catastrophic blow to livelihoods, jobs and growth.

The currency has depreciated significantly. Inflation is up, including on basic staples. Supply lines are strained. The banking system is in crisis. There are significant cash shortages and companies are struggling to pay employees.

Exports and imports are expected to plunge this year. Manufacturing operations have been affected by both the pandemic and the civil disobedience movement, and Myanmar’s ports have experienced periods of significant disruption.

According to some estimates, more than 600,000 jobs have been lost already, including in the vital garment industry, a major employer of women. Some international companies are pausing investments and joint ventures, especially those linked to military-owned businesses. New investors are likely to look elsewhere in the region.

Myanmar’s public health system is yet another coup victim. Public hospitals are shut or limited in the services they are offering, with health workers joining the civil disobedience movement in large numbers.

In the meantime, daily reported cases of COVID infections have been on the rise since late May, especially in northern towns bordering India. Myanmar’s small stock of vaccines is being rolled out slowly, haphazardly and with little transparency.

The Tatmadaw is attempting to force the country to return to some form of economic normality through intimidation, large scale arrests, torture and murder. This savagery may eventually succeed in subduing a brave population wanting a return to democracy, but at fearful cost.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has warned that Myanmar is approaching the point of economic collapse. It estimates that in a plausible worst case scenario, the twin shocks of the pandemic and coup could drive nearly half of the population of Myanmar into poverty, compared to the 24.8 per cent in 2017, losing a decade of hard-won gains.

COVID’s Long Shadow

Above all, the outlook for Southeast Asia’s economy – and for political stability and social cohesion – depends on region’s ability to contain the current outbreak and suppress new variants of the virus.

Tighter social distancing and movement control measures inevitably will affect second quarter results.

Malaysia has been forced into a nationwide lockdown by skyrocketing infections and a health system in danger of being overrun.

In Vietnam, some of the factories that have been powering its exports surge have been temporarily shut down or are operating at reduced capacity.

Thailand has already downgraded its own forecast for 2021, expecting the economy to expand by only 1.5-2.5 per cent this year (the IMF April forecast is 2.6 per cent growth).

Southeast Asian countries now desperately need internal discipline on mobility and social distancing measures, strong testing and contact tracing capabilities and as many doses of vaccines as they can get.

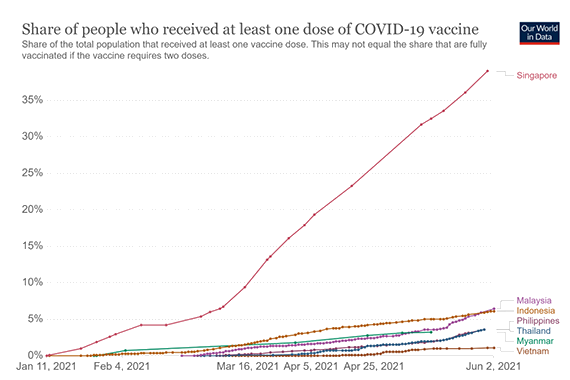

Except for Singapore, though, national vaccination rates in Southeast Asia remain very low.

Source: ourworldindata as of 4/06/2021

Shortages of vaccines and delays in delivering donated or purchased doses have slowed rollouts.

While global vaccine production has ramped up in past months, the developing world has to date come a very distant second to the monopoly of vaccines by wealthy countries (as of mid-May, only 0.3 per cent of the total vaccines administrated globally had gone to low-income countries).

India’s understandable decision to re-focus its huge vaccine production capability on its own urgent domestic needs has also created a significant shortfall of some 500 million vaccine does to eligible countries from the UN-backed, donor-funded COVAX facility.

India’s withdrawal from the export market could, if it is long-lasting, also affect the newly announced Quadrilateral Security Dialogue Indo-Pacific vaccines initiative.

Large scale vaccination programs in some Southeast Asian countries will also be difficult because of bureaucratic and funding constraints and large and/or dispersed populations.

Especially for the largest Southeast Asian countries, like Indonesia and the Philippines, and the poorest, such as Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar and Timor-Leste, keeping up with variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and continually vaccinating populations, will be a gargantuan task.

Vaccine hesitancy is a problem, with reasons ranging from concerns from Moslems that vaccines might not be halal to doubts about the efficacy and safety of Chinese-made vaccines.

Vaccine production will eventually increase sufficiently to overcome current global shortages. The International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations appears confident this could happen relatively quickly, especially as new vaccine candidates come on line.

Homegrown Southeast Asian vaccines from Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia are among those still in development. And Thailand will manufacture the AstraZeneca vaccine locally for itself and others in the region.

While these are hopeful developments, Southeast Asia is in a race against time and proliferating new variants to end the acute phase of the pandemic.

There is an urgent need for significantly boosted external support for vaccination programs, especially as much of the region will continue to rely heavily on donated rather than purchased supplies. Australian-donated AstraZeneca vaccines, for example, are central to Timor-Leste’s vaccination program.

Without new global sources of vaccine production and this additional donor support, it seems unlikely that most Southeast Asian countries will have vaccinated large percentages of their populations by the end of 2021, and perhaps not even well into 2022.

Source: ourworldindata as of 4/06/2021

Will this help come? In recent weeks, there have been welcome signs of the global ambition needed to accelerate vaccination programs in the developing world.

With vaccination rates rising steadily in the United States, the Biden Administration has announced its intention to step up global leadership on the pandemic, beginning with a down payment of 80 million donated doses. The Administration has said it will continue to make excess supply available globally.

At the 21 May EU-G20 Global Health Summit, the European Union announced it would donate 100 million doses of vaccines to low-and middle-income countries, including through COVAX. Major manufacturers also pledged additional “no profit” and “lower price” vaccines for low- and middle-income countries respectively.

And the COVAX summit in Japan on 2 June raised another $US2.4 billion, enough for COVAX to secure 1.8 billion free vaccines doses for lower-income countries in 2021 and early 2022.

This is a start, but developing countries are so far behind wealthy nations that there is more to be done.

Excess supplies of vaccines from wealthy countries need to be shipped urgently. In some countries, ramping up supply will need to be matched with help to actually get vaccines into arms.

More could done, including backing a temporary waiver of intellectual property protections on vaccines and removing restrictions on the export of raw materials that allow third countries to produce vaccines locally at scale. The Biden Administration has said it is “working with the private sector” to expand production of raw materials.

And despite the new donor pledges, there’s still an urgent need for more grant financing to fight the pandemic globally.

As the World Bank and IMF leadership have said, as much as $50 billion of financing is needed to achieve more equitable access for vaccines, tests and treatments.

Global attention and concern are understandably focussed now on India and neighbouring countries in South Asia. But India also stands as a stark warning of what can happen anywhere in the world when new variants rip uncontrollably through vulnerable communities.

Ramping up support now for Southeast Asia’s vaccine and public health programs is the best investment the world can make to save lives and ensure the region’s continued economic recovery and social stability.

[1] Statistics from the ASEAN data portal

About the Author

Richard Maude is Executive Director of Policy at Asia Society Australia and a Senior Fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute. Mr. Maude joined Asia Society after a 30-year career as an Australian diplomat and intelligence official. He is a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Director-General of the Office of National Assessments, and senior foreign policy adviser to Prime Minister Julia Gillard.